Volume 1, Issue 1 (2013)

Introduction to Bazin

In the first issue of Cinesthesia, four of our authors—Meyer, Hogan, Butkovich, and Ratliff—turn to the theorist whom many film scholars believe to be the father of modern film studies as well as the great polemicist who ushered film into the realm of academic discourse: André Bazin. Working in postwar France among such intellectuals as Jean-Paul Sartre and André Malraux, Bazin co-founded the highly influential Cahiers du Cinema and mentored such filmmakers as François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard, who, near the time of Bazin’s death, began the landmark French New Wave. Bazin’s influence on film during his short career was astounding. Director Jean Renoir wrote of the theorist, “He created a national art. After considering his writings I changed my own filming plans.” Similarly, François Truffaut, telling of the multitude of filmmakers who were present at Bazin’s funeral in 1958—including Cocteau, Bresson, Buñuel, Welles, and Fellini—proclaims, “At the moment of André Bazin’s death, we were all present at something truly rare: artists paying tribute to a critic!” (xiii).

Bazin was foremost a critic who engaged in an ever-active and vital discourse on the cinema of his time. For this reason, he never took the time to systematically lay out his theoretical perspective as did many of his predecessors. Nevertheless, Bazin’s essays indicate a clear and nuanced theory of the cinema—one that film scholars call “realist.” Bazin is a realist, however, not because he favors films that are “realistic” or that show life “as it really is;” rather, he is a realist because he argues that the art of film, as opposed to the other plastic arts of the Western tradition, has its physical basis in the real. Film, Bazin argues, succeeds in mechanically capturing brute reality—or the reality of the physicist—and because it has the unique capability to do so, it is likewise able to bring out the latent truths of the real. Film, then, becomes art through the process of framing, not manipulating, reality.

Interestingly, Bazin was the first major thinker of the cinema to argue from a realist perspective; in fact, his view of the cinema was in direct opposition to the major theorists who came before him. The early theorists, seeking to establish film as an art form, focused on how film differed from reality—that is, on how it could present an artist’s interpretation of reality. Correspondingly, such theorists focused on the process of editing, or montage, in their analyses of film. Bazin, on the other hand, argues just the opposite. He posits that the filmmaker should allow the unadorned filmic image, with all its inherent ambiguities, to communicate meaning.

Today, Bazin’s ideas remain highly influential and relevant to the theoretical discourse on the cinema, both in America and abroad. Yet, what is uniquely interesting about Bazin is that, though he effectively guided cinema studies into the university system, he never took part in its ascendance to that system. The bulk of Bazin’s work, instead, was done in conversation with filmmakers and critics at the time, concerning specific films and their particular effects. Because Bazin’s method of criticism and theorizing was so focused on individual films, applying his theories to contemporary films is likewise both challenging and rewarding. Explaining Bazin’s unique way of getting at deeply profound truths in his discussion of specific cinematic traits, film scholar Dudley Andrew writes, “This method [of criticism] makes reading Bazin exciting but it makes summarizing him extremely difficult, for no summary can capture that style of theorizing and writing which may be the most valuable thing we can learn from Bazin” (136). Accordingly, four of the following essays represent some attempts made by undergraduates to achieve that difficult but rewarding end. Indeed, the authors have inevitably chosen one or a few aspects of Bazin’s view of the cinema but, in sum, they will hopefully generate an open and vital discourse on film that Bazin, in his day, would have engaged in with great vigor.

Works Cited

Andrew, Dudley. The Major Film Theories. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976.

Print.

Renoir, Jean. “Adieu à André Bazin.” France-Observateur 13 November 1958: 455.

Print.

Truffaut, François. Foreward. André Bazin. By Dudley Andrew. New York:

Columbia University Press, 1990. xiii-xvii. Print.

Suggestions for Further Reading:

Andrew, Dudley and Hervé Joubert-Laurencin, eds. Opening Bazin: Postwar Film

Theory and its Afterlife . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011. Print.

Bazin, André. What is Cinema? Volumes I and II. Translated by Hugh Gray. Berkeley:

University of California Press, 2005.

Articles

"Little Miss Sunshine" and its Basis in Reality

Danica Butkovich

Untitled #1: "There Will Be Blood"

Mallory Quinn

Untitled #2: "Little Miss Sunshine"

Mallory Quinn

Untitled #3: "Paranormal Activity 2"

Mallory Quinn

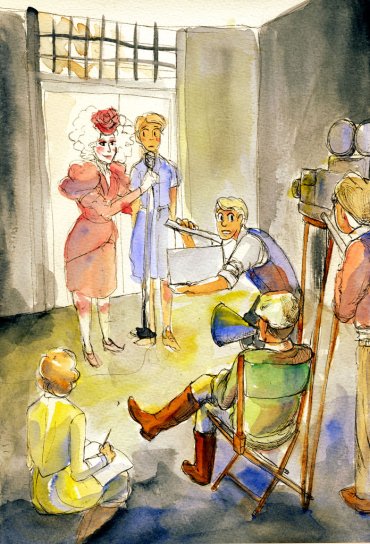

Untitled #4: "Director at the chair"

Mallory Quinn

Editors

- Editor-in-Chief

- Joseph Hogan, Grand Valley State University

- Editorial Board

- Nikki Martin, Grand Valley State University

- Kelly Meyer, Grand Valley State University

- Danica Butkovich, Grand Valley State University

- Faculty Advisor

- Toni Perrine, Grand Valley State University